Its worth playing the long investment game

Analysis of global bond and equity markets since 1991 reveals some of the secrets to successful investing during good times and bad.

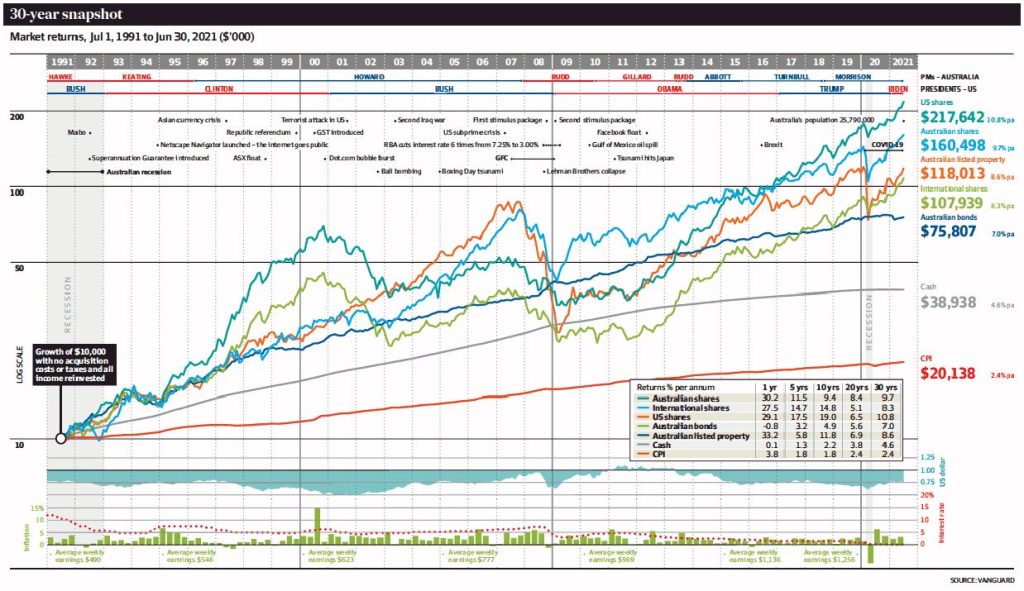

A snapshot of investment returns for the past 30 years reveals the gain from a diversified portfolio and the pain of trying to time markets and buy stocks just before prices go up or sell just before they fall.

A $10,000 investment in US shares at the beginning of 1991 – with income reinvested – would now be worth nearly $218,000 (or more than five times what the equivalent investment in cash would have made), an annual compounded return of about 10.8 per cent.

But someone who invested in US stocks in 2000 – when the dot.com boom was pushing the market to record highs and markets were irrationally exuberant – would have been smashed by the subsequent crash and taken 14 years to achieve a zero return.

The timing is as tricky now for investors, particularly retirees, who are attempting to generate an income from bonds and bank deposits.

In 1991, when a house in Sydney cost around $182,000, the Reserve Bank of Australia cash rate was 12 per cent and savers could earn double-digit returns on their savings. That helped generate the 30-year cumulative Australian bond return of 7 per cent and cash return of 4.6 per cent.

But the current cash rate is around 10 basis points and average bonus saving accounts are paying around 60 basis points.

Balaji Gopal, head of the personal investor business at Vanguard, the global fund manager with around $10.6 trillion under management and which compiled the annual performance chart, says: “Short term, it is very difficult to time markets. Our view is investors should be focused on the long term, stay invested and not react to adverse markets by pulling out.”

Shane Oliver, AMP Capital’s chief economist, says the outperformance of growth assets – which are considered higher risk because of their volatility, compared to defensive assets such as cash and bonds – can be traced back to 1900.

“Over long periods of time, assets like US, global and Australian equities produce higher returns because of their leverage to growth in the economy,” he explains. “And their higher returns compound to big differences in wealth generation over long periods of time.”

Matthew Lemke, income portfolio manager at Prime Value Asset Management, adds: “Diversity is the most powerful of all investment principles because markets are unpredictable and there are proven benefits to spreading risk.”

Financial advisers recommend investors avoid the risk of having to time the market, through a popular technique called dollar-cost averaging, which involves investing the same amount at set intervals over a long period and allows bigger purchases on market dips.

There’s been no shortage of thrills and spills during the past 30 years as wars, terrorist attacks, accelerating globalisation, a global financial crisis (GFC), transformational technologies and pandemics caused markets to soar and slump, affecting the comparative performance of different asset classes in myriad ways.

Roger Montgomery, chief investment officer of Montgomery Investment Management, explains: “It is not surprising over longer periods to see the value creation from owning businesses reflected in the performance of major stock indices. What is surprising is how long it took the MSCI World ex-Australia index to recover its losses after the GFC and begin outperforming Australian government bonds.”

After dipping below bonds in 2007 – which is when the GFC started – it took a decade for international shares to outperform.

“For those who invested in shares any time after the GFC and before 2011, you would have trounced bonds. And that’s a useful lesson – you’ll do well owning quality businesses, and you’ll do even better if you buy those businesses at a rational price, which is sometimes when everyone else is running around with their heads cut off.”

The outlook is more tricky for investors with only a short investment horizon who are worried that a big dip could affect their retirement income, especially when there are regular expenses that cannot be deferred.

Oliver says: “The key for an investor is to make the most of the power of compound interest via growth assets, but diversify and allow for your tolerance to risk – or short-term volatility – in structuring your portfolio.”

He adds: “If an investor has only a short investment horizon, does not like volatility and/or has a low balance that they cannot afford to see fall much, then it makes sense to include a greater exposure to defensive assets like cash and bonds – but recognise that over decades this will likely produce lower returns than a portfolio loaded with more growth assets.”

Alex Jamieson, a financial adviser with AJ Financial Planning, says 30-year returns on Aussie bonds of 7 per cent and a cash return of 4.6 per cent “will likely be a distant memory”.

Jamieson adds: “Our expectation is that investment-grade Australian bonds over the next two to three years will be well below 3 per cent.”

Prime Value’s Lemke says those needing a stable income stream and capital preservation will need to consider multi-asset alternatives.

“Adding income funds which invest in unlisted securities provides ballast and diversity in an investment portfolio,” he adds.

Paul Moran, principal of Moran Partners Financial Planning, says: “The fact is that while most investors’ actual time frames – especially for superannuation – are more than 30 years, it is highly unlikely that they would remain invested when the returns don’t meet expectations for some time.”

Rather than knee-jerk reactions to switching around portfolios, he says it’s worth investors seeking expert advice to interpret markets, understand volatility and review long-term expected performance. That way, a portfolio can be tailored to individual needs.

Source: Australian Financial Review